Provence / Mont Ventoux

Day 1: 17th April ’12

Distance: 59.61 miles

Total Distance: 59.61 miles

Route: Orange » Remoulins » Pont-du-Gard » Tavel » Chateâuneuf-du-Pape » Orange

Sunday evening, and most of Monday, we spend making the long drive from Bergerac airport to Orange where we aim to set up base. The weather is foul en-route with temperatures as low as 3-4 degrees and gale-force winds; the omens for a happy time in Provence aren’t promising.

Today, Tuesday, we head out early for a good leg-stretching ride in advance of an attempt at Mont Ventoux tomorrow. Beautiful crisp blue skies are a welcome sight, although the winds continue to blast and howl about our heads. We make lightning progress toward the ‘Pont-du-Gard’ with the aid of a forceful tailwind.

The ‘Pont-du-Gard’ is a spectacular sight indeed; one of the rare occasions when a famous monument actually meets or even surpasses your expectations. During yesterdays drive down to Orange we made a minor detour to view the Norman Foster designed ‘Millau Viaduct’. A beautiful, daring and superbly elegant bridge, the structure is in stark contrast to the huge stone blocks used in the construction of the ‘Pont-du-Gard’.

Of course the construction of the Millau Viaduct had the benefit of computer-modelling, modern materials and a couple of thousand years of additional knowledge – but I can’t help thinking that the Romans ‘knew their onions’ quite well and would have given old Normski Foster a run for his money.

We take a slightly circuitous route back to Orange, over some considerable climbs, in order to lessen the effects of the strong wind, now reversed and blasting directly at us.

This is world-famous wine country and we pass through thousands of acres of prime ‘Cotes-du-Rhone’ vineyard real-estate. The pretty village of ‘Tavel’ is renowned for possibly the best Rosé in the world; however, we are not sufficiently interested in this pink drink and bike on swiftly to something a little more full-bodied.

At Chateâuneuf-du-Pape we have a small ‘degustation’ of the local brew and buy only a few bottles as we are limited to what we can carry on our bikes. A little wobblier on our pedals than on entering into the town, thankfully it’s not too far back to Orange where we rest up and eat well in preparation for the ‘Giant of Provence’ tomorrow.

Day 2: 18th April ’12

Distance: 28.42 miles

Total Distance: 88.03 miles

Route: Orange (transfer) » Bédoin » Saint-Estève » Chalet Reynard » Mont Ventoux » Bédoin

It’s a short drive from Orange to Bédoin where we plan to start the ascent of the ‘Ventoux’. The weather is clear this morning and the vast mountain, which stands proudly alone in the Provençal landscape, is visible from miles and miles away.

There are three routes up to the summit. The first, a Southerly route up from ‘Sault’, is by all accounts merely painful. The North-Western route from ‘Malaucène’ is deemed by most to be extremely painful. The third route from Bédoin, and the decided route that we will use, is usually described as being extremely, extremely painful.

The Bédoin route is the ‘classic’ route – and we decide that if it’s good enough for professionally trained, immensely fit Tour riders, then well, it’s good enough for us…

Some research completed beforehand had revealed that the climb up through the forest from Bédoin would be murderous. I had heard it referred to as the ‘forest of doom’ and now I fully understand why. The steep gradient a solid, unrelenting, merciless 9-10% average. There is no chance to catch your breath, and the thick forest cover offers no clue to the progress (if any) that you are making up the mountain. I can hear my heartbeat pounding in my eardrums and am forced to stop at regular intervals just to get my heartrate down slightly.

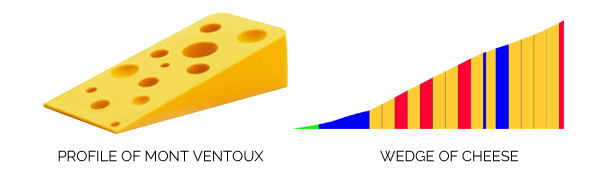

On leaving Bédoin, the summit of the Ventoux is signed as being a mere 22km away. This lulls cyclists into a false sense of security I think; 22km (or just under 14 miles) would seem easily ‘do-able’ to anyone with a little experience. I’ve been up several mountains with climbs almost twice that length. However, every single metre is hard-fought on the Ventoux; this beast gives away nothing, absolutely nothing. The profile of the mountain is not unlike a giant wedge of cheese and it’s a constant slog all the way to the very top.

Eventually, and to my considerable amazement, I finally exit the forest of doom and reach ‘Chalet Reynard’ where I had arranged to wait for Dad – who had insisted that I head on without him. I wait for a short while, but am totally convinced that the 76 (nearly 77) year old cannot possibly make it this far, and so head on further up the mountain.

Shortly after the ‘Chalet’ the forest cover drops away and the mountain of Tour-de-France legend becomes visible. This is the bald, barren, windswept limestone volcano of every cyclists dreams… and nightmares.

One thing about the Ventoux cannot be criticised once you are at this stage: there are no false summits. The top of the mountain is clearly visible and the tower at the very summit acts as a beacon to both taunt and draw you inch by inch further up the mountain. Luckily, the weather holds as I push further on up the slopes. I’m mindful that the weather could change at any moment and that the ‘Ventoux’ (from the french word ‘Venteux’ – ‘windy’) has been known to literally blow people off the mountain.

Eventually after more slog and painfully slow progress I reach Tom Simpsons memorial, a mere kilometre from the summit.

The memorial to Tom Simpson (who died of exhaustion on the mountain during the 13th stage of the 1967 Tour-de-France) is a moving and sobering reminder of the power of this mountain. It also serves to illustrate the ability, resolve, physical power and mental strength that professional riders possess in order to climb mountains like this during competition. It’s one thing to make a climb on the Ventoux at your leisure; another thing entirely to have to race up it in the company of the greatest athletes on earth.

2 hours and 25 minutes on the road and I finally reach the summit. I am rewarded with the most fantastic views – as far as the eye can see, to the Alps in the east and beyond. I take a few photos for the scrapbook and decide not to hang around as the weather is looking menacing. I fly down the slopes that had taken such effort to climb and head off in search of Dad whilst trying to recount the basic first-aid I had learnt at school.

To my considerable amazement the CPR is not required and I’m forced to slam my brakes on just 2½ to 3 miles down from the summit. Dad is still plodding up the mountain and looks well! After discussion, Dad decides not to continue up to the top despite being so close. Although only a couple of miles from the top, it still could take 30-35 minutes to reach it, and with the weather looking sketchy Dad decides that he’s more than satisfied with his efforts. I’m impressed. Very impressed. I feel confident that very few of my own peers, some 40 years younger, could have reached the same height up the mountain as him.

We head back down together and back to the carpark at Bédoin. Bikes are quickly packed away, we change out of our cycling kit and then we drive 350 miles back toward our lodgings for the night. By the time we get there, late at night in torrential rain, we are tired but satisfied. Yet another great ride in the bag; what’s next?